[Ap]Parent Bodies

![[Ap]Parent Bodies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ac2470e4b003351c03e69e/1547927992724-R0UPUDM37NJXHQ4LVESO/Marie+McInerney+-+Artspace+-+Dec+2018-1105-Edit.jpg)

[Ap]Parent Bodies

2018 | light, silk, atmosphere, plaster, flax paper, metal leaf, beeswax, concrete, cotton, plastic, and meteorite fragment

![[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.3](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ac2470e4b003351c03e69e/1568644112566-EQZER59KH1BFU7D6DLG6/Marie+McInerney+-+Works+-+Aug+2019-1405.jpg)

[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.3

2018, canvas, paint, metal leaf and scribe

![[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.2](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ac2470e4b003351c03e69e/1568644130742-54KSSOFNPBWE9CUHRNVJ/Marie+McInerney+-+Works+-+Aug+2019-1425.jpg)

[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.2

2018, canvas, paint, metal leaf and scribe

![[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.1](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ac2470e4b003351c03e69e/1568644148295-Y004XM37E8NWWTQX7PMR/Marie+McInerney+-+Works+-+Aug+2019-1427.jpg)

[Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.1

2018, canvas, paint, metal leaf and scribe

![[Ap]Parent Bodies: Strata Series](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ac2470e4b003351c03e69e/1547932490438-L4JPIXYS2E5H00YBW0N6/Artspace+-+CSF+Awards+-+Oct+2018-5933-2.jpg)

[Ap]Parent Bodies: Strata Series

Stone and Blood of Gods

Essay by: Exhibition Curator Jennifer Baker

During droughts, plants exude an oil that is absorbed by the clay in rock and soils. This oil is thought to slow the germination of seeds, improving their potential to successfully grow when rainfall is more abundant.[1]Once it does rain, water releases the oil into the air along with geosmin, and the combined scent of these compounds creates petrichor, or put simply, the scent of rain.[2]

The absence of liquid water and gravitational effects in space makes rainfall as we understand it on Earth impossible. However, in the ice-giant worlds of Uranus and Neptune, highly pressurized molecules of methane crystallize to form tiny diamonds that rain down through the permeable gaseous surface and into the interior of these strange planets.[3]While diamonds on earth are relatively rare, extraterrestrial diamonds are quite common. These microscopic nanodiamonds are often found in meteorites, and samples prove that they retain a readable record of their formation,[4]tracing a long and violent history of being ejected from a star into interstellar medium, travelling through the formation of a solar system, and being incorporated into a planetary body that was eventually broken into pieces—meteorites that flew billions of miles through space and time to crash onto the surface of this world.

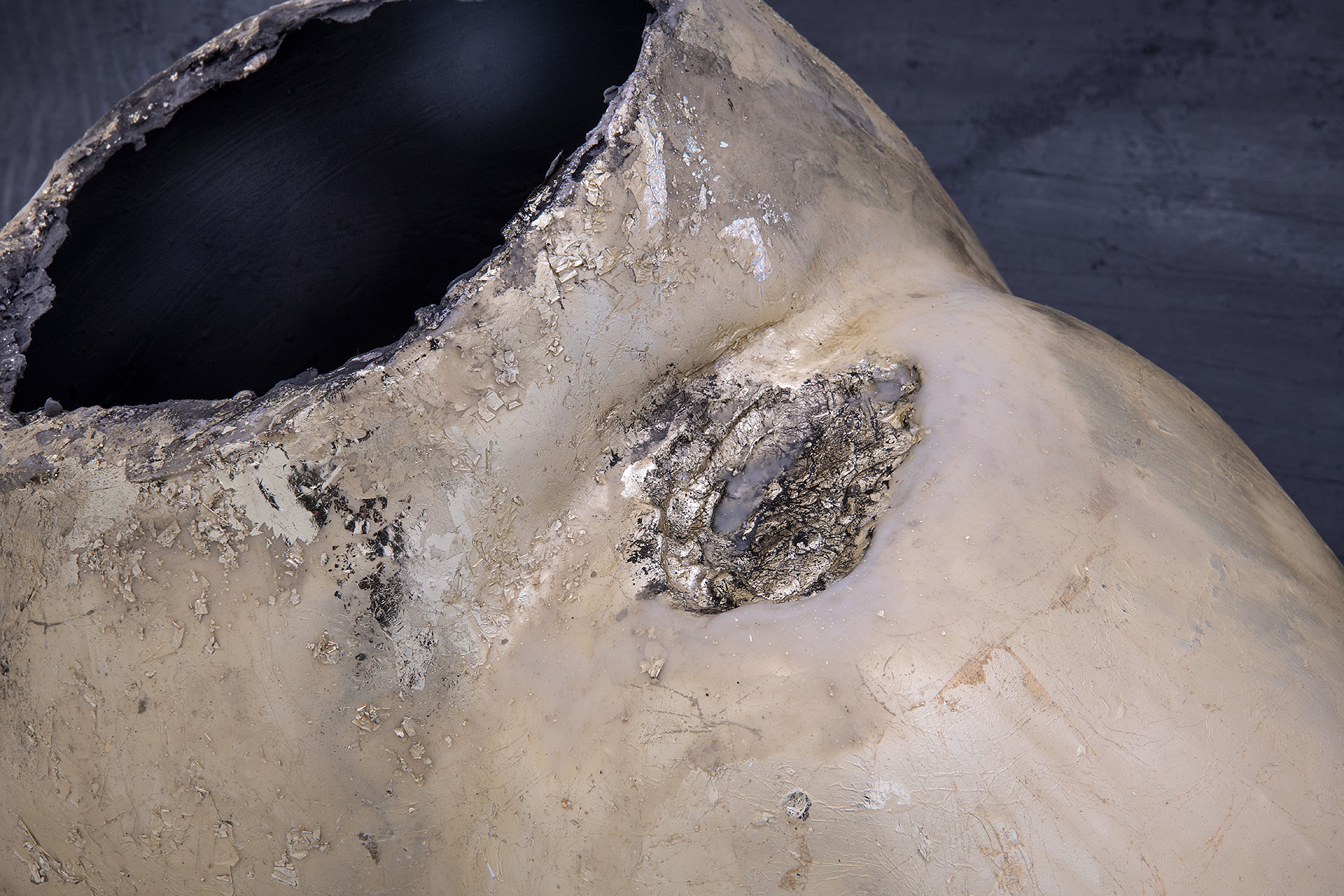

Set within Marie Bannerot McInerney’s site-responsive installation [Ap]Parent Bodiesis one such meteorite fragment—a 4.5-billion-year-old specimen that landed approximately 5000 years ago in present-day Argentina and was procured by the artist via the internet through a mineral dealer in Minnesota. The palm-sized reflective metallic fragment is placed on a dark plinth alongside a much larger golden eggish form that could as easily be an alien seed pod as a precious mineral geode as some kind of vacated incubator for an unknown animal form. The plinth, also made from material thatappears unnamable to theviewer, could as easily be volcanic rock as it could be industrial flooring as it could be a whale’s hide, and it sits on a brilliant white grid of tiles, lit from above by a fixture designed to outline the measurements of the plinth directly below it.[5]Between these two parallel geometries—which take up two stories of architectural gallery space—are five giant swaths of sheer fabric, dyed in gradient from grey to white, and slung from the walls into a sagging belly that hangs above the plinth, leaving just enough room for a human body to stand. A cool light is diffused through these gradient tones until it reaches the ground and permeates the space in a dim, petrichor-hued stillness.[6]

The artist’s inventive and masterful command of materials as well as her decade-long career in theater, where she hand-dyed costumes and props to create imagined worlds, is on display in this installation which functions as a kind of stage set. In fact, it is a stage within a stage, and our own bodies are invited to participate as actors, as long as we are comfortable—or willing to engage in the discomfort of—having no script. On stage already are two character actors and/or strange props: the meteorite fragment and Eggish. Footsteps are audible on the gleaming white floor tiles as we circumambulate the mysterious plinth, and it becomes clear once we have moved through the installation that Eggish is a vessel, punctured or maybe detonated or possibly destroyed from within. We are drawn toward the uncanny hole and sense its aurally resonant and smelly void, a darkness that interrogates recognizable depths and boundaries.

Theorist Timothy Morton poses that the reason we humans, as a species, have not been able to successfully address the demise of the planet is that we have attempted to prevent the end of the world; we should instead accept the fact that the world is always already-ending and address these issues from such a temporal understanding.[7]As climate change thaws the Siberian permafrost, for example, there is exciting potential to investigate links to our distant pasts in the preserved human and animal bodies that were frozen in time thousands of years ago. But this thawing also predicts terrifying futures: folding and warping landscapes that release carbon into the atmosphere and create a feedback loop of arctic warming in which toxic mercury and long-dormant microbes might also begin to escape from the frozen ground, accumulating in the food chain and proliferating ten-thousand-year-old viruses capable of eradicating entire populations that are without immunity. In her research, McInerney links these phenomena of the Anthropocene to the final scene of Shakespears’s Romeo and Juliet, when Juliet wakes from her drug-induced slumber to find Romeo dead from suicidal poisoning, ingested in tragically mis-informed mourning. Upon understanding the events that have taken place, the grief-stricken Juliet stabs herself with her lover’s dagger so that she might join him in death. McInerney sees the possibility of this theatrical tragedy of dormant potentials and deadly misunderstandings to play out on a global scale with unimaginable environmental impact. Her work provides a spacetime where we might psychologically prepare ourselves to encounter what we learn when this ended earth wakes.

To accompany her large-scale installation, McInerney has created three relatively small drawings titled [Ap]Parent Bodies: Stratum 1.1, 1.2, 1.3.On perfectly square and leather- or rubber-like substrates of meticulously painted and sanded canvas, the artist has incised the smooth black surface with a scribe to demarcate aerial views, rendered in very fine line, of various elements in her installation: the grid structure of the floor, the dark and textured plinth, and the square perimeter of the light fixture. These drawings maintain McInerney’s organic and materially complex signature with a modest but distinct dusting of metal leaf, calling to mind both a deep night sky with a galaxy full of distant and potentially dead stars, and the black and gold enigma of Eggish. We remember that a void is an abject container for what we claim to know, wherein projections only return questions. What tragedy has taken place here? Is what we see a hole or whole? Shall we measure “end” as whenor where?

[1]Bear, Isabel Joy; Thomas, Richard G. "Petrichor and plant growth". Nature. 207.5005 (1965): 1415–1416.

[2]Petrichoris a name coined by Australian researchers, taken from the Greek petra(stone) and ichor(blood of gods). Bear, Isabel Joy; Thomas, Richard G. (March 1964). “Nature of argillaceous odour”. Nature.201(4923): 993-995.

[3]Ross, Marvin. "The ice layer in Uranus and Neptune—diamonds in the sky?". Nature. 292.5822(1981): 435–436.

[4]Davis, A.M. “Stardust in Meteorites”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108.48(2011): 19142-19146.

[5]The material of the plinth is a textile invented by McInerney through extensive testing, which the artist began in her studio in 2014. A complex mixture of concrete, pigment, elastics, and other treatments are applied to a machine-knit substrate, producing what is essentially a flexible concrete fabric. Upon learning of this material, Jacob Canyon (the designer of this catalogue), coined the term “Bannerite,” and I have since adopted the name as an apt description of this mineral-like substance.

[6]I am suggesting that the artist’s treatment of “atmosphere” (listed as a medium in the artwork’s object label) creates a pale green capable of evoking a synesthetic response, a color that smells of rain.

[7]Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Photo Documentation by: EG Schempf

*Special thanks to studio intern, Josie Eckerman for her assistance with this project.